Shows

Thank you for taking time to read more about past shows as well as news about upcoming shows. While I do need to sell my work, I do see a larger role for art in general: to tell stories through imagery that can captivate beyond words. My shows are meant to be more than just a collection of paintings available for purchase. Together, the pieces are curated to tell a broader story, which I feel is the real purpose and power of being an artist.

Upcoming Shows:

August 2024: Bear Gallery, Fairbanks, AK:

“Bouquet All Day: Flowers for My Friend, Fairbanks”

September 2024: Homer Council on the Arts, Homer, AK

“Death of Retail”

Previous Show: Season of Change

International Gallery of Contemporary Art, Anchorage, AK September 2023

“Season of Change” is a collection of oil paintings that tell a story of the not only the beautiful changes that occur around us in Nature but also of the inevitable change that occurs within us. Although we witness and appreciate external seasonal changes for their beauty, as humans we are also aging like the leaves around us. As I turned 50 in 2022, I entered the autumn of my own life, and these paintings reflect my emotions about the inevitability of our final season.

Season of Change is presented in 3 sections: Stand Still, Autumn, and In Everything.

“Stand Still” includes 15 paintings of a landscape, painted from the same spot over a period of 13 months. The paintings aren't meant to be maps of the landscape but rather an artistic expression of the constant evolution of change around us. While we go about our daily lives, so do the birds, the trees, and even the water. If we ever stood still, this might be what we would observe.

“Autumn” includes 5 landscape paintings depicting autumn scenes. In 2023, I turned 50 and entered the autumn of my life. These beautiful landscapes remind us of the changes to come in our own lives.

“In Everything” is a series of 9 paintings that remind us that there is an inevitable change in all living things that usually ends in death. One of the paintings in this section is a self portrait titled “Turning 50 Sucks: Self Portrait of the Artist”

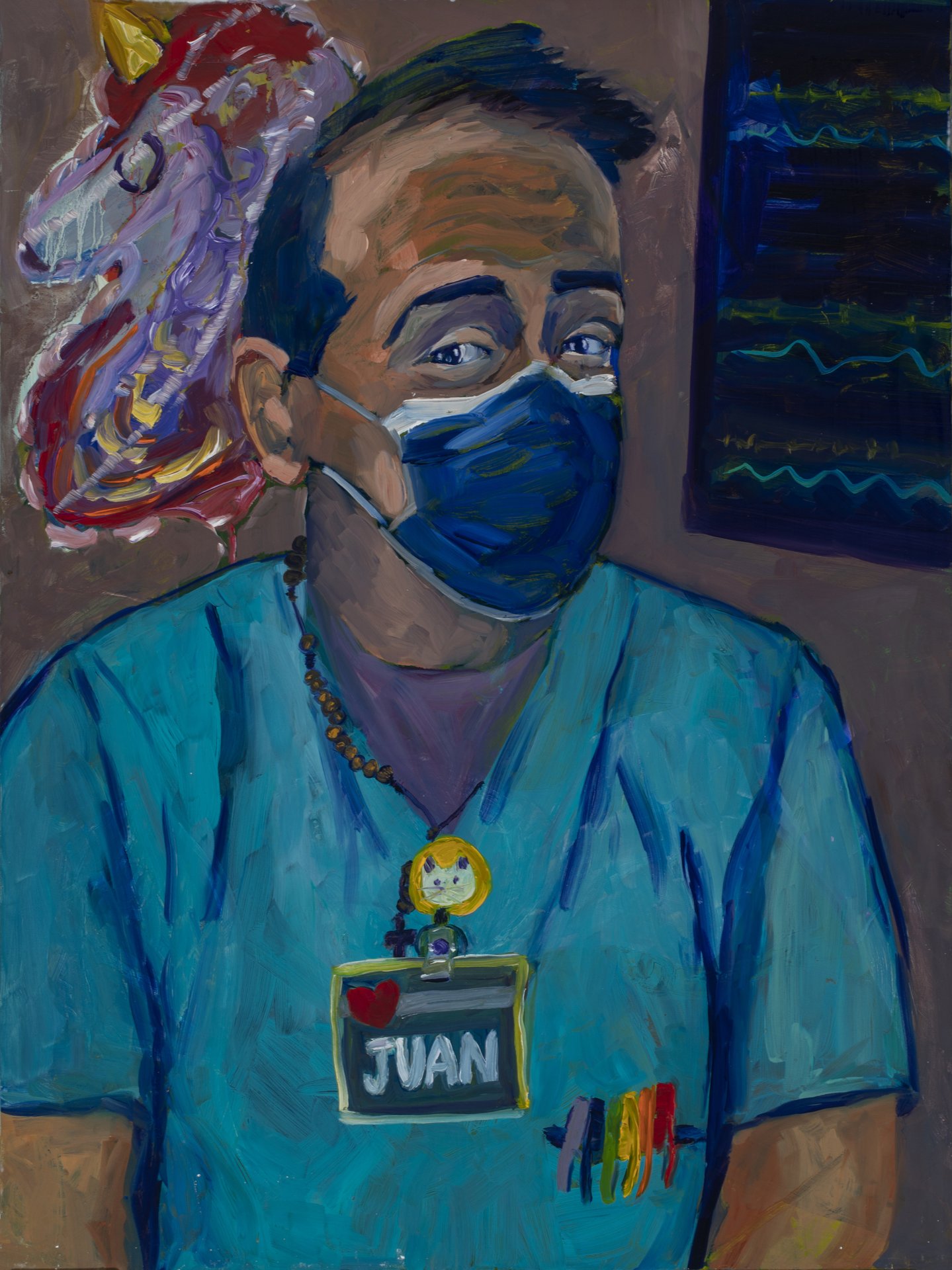

Previous Show: Mind of a Healthcare Worker During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Homer Council on the Arts, Homer, Alaska. January 2022

My first art show, “The Mind of a Healthcare Worker During the COVID-19 Pandemic” garnered international attention from numerous media outlets including US News and World Report, Seattle Times, Houston Chronicle,Toronto Star, Ottawa Herald and Vietnam Art News.

The Mind of a Healthcare Worker During the COVID-19 Pandemic:

“I have been an emergency medicine physician in Anchorage, Alaska, working at the state’s largest ER since 2005. In 2018 I took on the additional role as the business manager for my group of 40 physicians. In what little spare time I had, I would dabble in painting. In 2019 when I challenged myself to paint on a daily basis, I never could have predicted that the stressors I dealt with from my unique perspectives - of not only caring for patients as a frontline healthcare worker but also caring for emergency medicine physicians - during the pandemic would end up on canvas. Initially I was painting things around me – nurses, techs, N-95s. But as the pandemic wore on, my emotions saw their way onto canvas. These sometimes very raw paintings reflect a turbulent, stressful time for all of us, and so the viewer may find solace in something I have presented here.”

— Sami Ali, Artist Statement

This link will take you to the artist talk I gave about the art show and was given at the First Friday Reception, January 7, 2022 in Homer, Alaska.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9hs3NOj7GwY

The show consisted of 45 original art works - 42 paintings and 3 sculptures - created during the first 18 months of the pandemic.

THE SHOW IS DIVIDED INTO 6 CHRONOLOGICAL SECTIONS:

WHEN WE WERE HEROES

December 2019: Pre-COVID-19

“There’s a virus in China. I think we need to be worried,” my husband said. I wanted to ignore him but on the flight home from our 2019 holiday vacation, we wore masks on our flights - we were the only ones on the plane wearing masks and we looked like hypochondriacs. A few weeks later we knew Wuhan was the epicenter of the infection. Shortly afterwards, I was notified that there was a plane coming from Wuhan evacuating American citizens, and the plane was stopping in Anchorage. I was working in the ER that night, and we were nervous. Would anyone be sick and need to get off the plane, potentially spread the virus? What was this illness anyway? How bad would it be? Would it be like Ebola where death is nearly guaranteed and hazmat-level personal protective equipment (PPE) would be required? We were looking at PPE options and looking at our staffing options. How much time would we have before this illness came to Alaska?

Then, it happened. A patient at a Providence hospital in Washington became the first American on US soil to be diagnosed with the virus. Still, the virus seemed contained. It was in Washington state, not here in Alaska. We’re isolated here in Alaska. “We’re different” in Alaska.

March 16, 2020: Spring Break

We were holding a meeting of our emergency medicine physicians at Providence Alaska Medical Center on March 16, 2021 when we got THE call. Someone in Anchorage tested positive. They were going to “isolate,” but it had finally arrived in Alaska. Travel needed to stop. Each of our emergency physicians who had been away on Spring Break suddenly couldn’t return to work because they might be bringing the virus back to Alaska - they would need to isolate for 14 days. Instantly there was a staffing shortage, and there was confusion and fear. But everyone seemed to want to help in any way they could. Families stayed isolated from people outside their small bubble. My daughter returned from college and never had a graduation. “We are in this together” we said. I was watching daily national and state news conferences. I worked every day for 30 days straight reading anything and everything I could find about this virus, what PPE is needed, how the virus is thought to spread, and how to keep our staff safe. Why are the folks in China wearing more PPE than we are? Why are they running out of PPE in NYC?

Then it got real. A fellow emergency medicine physician in Washington is dying from the virus. He needs a serious treatment called ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) which is essentially a heart/lung bypass machine. That means he’s REALLY sick. The emergency medicine community is very small – you invariably know a nurse who once worked with that doctor in that small town long ago – so it felt like a family member had gotten sick. How did he get it? Was he wearing the right PPE? Would he live? How much risk are our doctors and nurses at? Were we doing enough to protect our healthcare workers? Then an opthalmologist in China died. How had an ophthalmologist contracted it? Through touching someone’s eyes?! Then nurses in New York died. Suddenly because healthcare workers were risking their lives to take care of patients, We Were Heroes. Scared heroes.

I was overwhelmed to see the tributes to healthcare workers in those first two months, from New Yorkers clanging on pots and pans every night at 6 pm, to signs hanging around the neighborhoods, to community food donations in our ER. It was appreciated, emotional, and heartwarming.I also saw how different healthcare workers approached the pandemic differently.Some had the ‘Hell yeah, we’re going to beat this’ attitude.Others were scared for their lives, especially our pregnant co-workers who were also scared about the unknown congenital issues with COVID-19. It was terrifying to see our medical colleagues around the country coming down with the very illness they were there to help with.Yet day after day with all the unknown risks they might face, these medical workers would don the PPE and help their patients because it was just part of the job.I couldn’t believe how scared they were for themselves but yet how unrelentingly brave they were for their patients. They really are heroes. And there were some who even had the extra capacity to bring a smile to others.

2. PREPARING FOR A PANDEMIC

April 2020: Hunker Down. Wear A Mask. Sanitize. Get Tested.

Get tested. But where? The 3 Anchorage hospitals united and stood up a drive thru COVID testing center. The first time I saw one of the test centers I was kind of in awe. It had appeared rather quickly, seemingly overnight, and the line of cars was sometimes so long it wrapped around 4 city blocks. It was still winter, yet these Alaskan nurses stood out in the snow to swab people who thought they might have the illness. Heroes! As the pandemic went on, supply chains dried up. There weren’t enough test kits. If a patient had obvious COVID-like symptoms we told them to go home and isolate for 14 days and come back if they became worse Alaska was making their own test kits.

People were home hunkering down. Everyone had a greater appreciation for family and friends. We watched daily news conferences. We spent our days at home baking bread, doing puzzles, and gaining the “COVID-20” pounds. People were using drinking alcohol as hand sanitizer. Then one day there was no toilet paper on the shelves.

Then there was no PPE. We saw the nurses in New York City wearing garbage bags as they didn’t have gowns. My emergency medicine colleagues in Louisiana wore raincoats when they ran out of gowns, washing them in Clorox after a shift. In Alaska, it was the N-95 that was in short order. We started having discussions about how we would recycle these particle-filtering masks that we used to protect us during ‘aerosol generating procedures’ such as nebulizations and intubations. These N-95 masks that pre-COVID would have been worn once a year for a suspected tuberculosis patient then throw away immediately were now in scarce supply and we didn’t know when we’d get more. Can we recycle them? Can we bake them in an oven? Can we nuke them with UV rays? I was adamant that we could not have a situation where we didn’t have masks for our healthcare workers. We had to protect them so that they could help others. I was fearful that one of our doctors would be on a ventilator like the doctor we knew in Washington. We don’t have a treatment much less a cure yet, so would they survive? The fear was real.

Most citizens knew that if they stayed home, away from others who might have COVID-19, they would not be exposed to COVID. But my colleagues had to come to the ER where they not only would be taking care of multiple sick COVID patients in a day who would expose them to risk, but they were also doing the most high-risk procedure – intubation. During intubation, the doctor’s face is usually within inches of the patient’s mouth as the doctor inserts a breathing tube into the patient’s airway to artificially breathe for the patient. Still short on N-95’s ,we were now wearing a surgical mask (which were more ubiquitous) over the N-95’s to keep the N-95s clean. Talk about extreme anxiety. If you had to intubate someone, you were fearing for your life. We definitely needed N-95 masks. Hospitals were talking about baking the masks in ovens to clean them, then recycle /redistribute them. I couldn’t stomach the idea that I might have to tell our physicians that they would have to wear someone else’s re-used mask that had gone through a (questionable?) cleaning process. We had to think of something.

I gave our physicians 10 paper lunch bags each, and three N-95 masks each. They were asked to wear one N-95, then afterwards place it in a brown paper bag, mark off a number on the bag indicating that the mask had been used, and then use the next mask in their rotation on their next shift. Yes, they optimistically got 10 bags and only 3 masks each. Knowing that supplies were running low, most physicians had saved their old masks as well, so most physicians had 4 or 5 total masks. (Personally, I had 7 masks in my queue). The physicians could then work at least 3 shifts before they’d have to wear the same mask for a second time, giving time for any virus particles on the mask to die. And they could hopefully use each mask up to 4 or 5 times before it got too limp, dirty or ill-fitting to use again. That would be 15 shifts…. Enough to cover a month and then hopefully we’ll have a solution for the mask shortage. But at least they’d have a mask, and one that only they had worn before; not one worn by a stranger.

We started seeing sicker and sicker patients in the ER. They were very short of breath, had low oxygen saturations, and needed ventilators. Once they got put on a ventilator, it was clear that we didn’t really have a cure for them. Unlike other viral illness, these COVID-19 patients were on ventilators for weeks at time - some for months. We don’t have that many vents in Alaska. The Italians were out of ventilators and dying. Why them? What didn’t we know yet about the virus? What if the healthcare workers get sick in the line of duty? Will there be a vent? Most of our doctors have young children and they feared leaving family behind. Stress and fear and concerns for safety were my world.

3. PPE PROBLEMS

Summer 2020

There was so much going on politically in the USA as elections were approaching. Honestly, I hardly had time to engage the national news but there was no escape from it. At this stage we were still using the brown paper bag system for our N-95s. We weren’t just wearing N-95s, we were wearing surgical masks on top of them. And surgical caps, and gowns, gloves, and faceshields if we had really sick patients. In a routine ER shift, you’d see about 8-10 COVID-19 patients who were super sick, which meant that they likely had a high viral load. This implies that if you got too close to their airway and they breathed on you that you were more likely to get the virus. So we were all wearing our double layer of masks for the entirety of our 10 hour shifts, most of us foregoing food and drink for those 10 hours. It was time consuming and suffocating to wear the garb but it had to be done if we were going to stay safe. The good news was that it was summer and Alaskans were allowed to gather outdoors. Things were status quo, so I finally had some time off in the late summer; but as my ER shifts approached, I had anxiety just at the thought of putting on another N-95 mask for 10 hours. Then, one day I had a meltdown when telling my husband that I didn’t want to go to work because my ears hurt sooo bad at the end of a 10 hour shift because it felt like the mask was ripping off my ear. This boiling frustration led to the next series of paintings.

4. A VACCINE IS COMING

September 2020

There were whispers about a vaccine. OMG! Really?! Hooray! Can this be too good to be true? It’s too fast for a new vaccine to be developed , isn’t it? I did weeks of research, attending meetings, and essentially reading anything I could about the vaccines. Turns out that this SARS- CoV-2 virus likely came from a lab in Wuhan, China, so the genetic code was already known and immediately released on the internet- there did not have to be years of genetic sequencing or months of requesting the release of information. And better yet, researchers who had already developed an mRNA medical technique found a way to make an mRNA vaccine. The mRNA vaccine would be in and out of your body’s system in hours, leaving your body equipped to mount an immune response if you contracted the virus! YES! It’s the Tesla of vaccines AND it works! I felt like Jonas Salk’s angel was looking over us. We don’t have to wait another year for someone to develop a live attenuated virus! We have a vaccine! How can I get one? How can I get one for all the healthcare workers I know? How can my 88 year old father-in-law get one, because he hasn’t left the house in 8 months? I’m so excited that everyone will be safe from this terrible virus! No one will be sick! Hooray! I won’t have to worry anymore about my colleagues! This is amazing news! I couldn’t contain my excitement! Vaccinations started in December and by January the doctors and nurses that we work with were fully vaccinated. We could walk around without masks in the ER, something we hadn’t done in a almost year. We could hug one another again. We finally felt safe. The fear and dread of coming to work was gone. It felt like you were wearing an invisible coat of armor! Whoopie!

5. THE BATTLE RAGES ON

March 2021

We were thankfully vaccinated. Safe. The vaccine was like a shield that we wore proudly and were excited that everyone would soon be protected. None of the physicians were getting sick, so the vaccine was working. I went back to painting daily landscapes plein air. People were intermingling, no longer afraid to be around others. I knew we weren’t off the mountain but that we had thankfully passed one peak. I didn’t know there would be another taller peak ahead, one that would be harder to overcome.

July, 2021: The Surge

It was strange to hear that people weren’t getting vaccinated. Some were taking ivermectin. At the same time, suddenly the ER was getting busier and busier. What was happening? So many more patients were coming in. Chest pain. Shortness of breath. Most people didn’t just want to know if they had COVID-19 – they assumed they had it. They wanted to know if they had ‘severe COVID-19’, whether they needed to be hospitalized, oxygen or even a breathing tube. Yes it is true that the vast majority of the patients who were being seen for concern of COVID-19 were unvaccinated. They were flooding the ERs and so there was a shortage of beds for other patients – patients with heart attacks, broken bones, sepsis. It became overwhelming having so many patients converging on the ER week after week. Physically it was challenging to manage the volume of patients, mentally it was difficult to manage their illnesses, but emotionally it was very difficult to understand the public health aspect of preventable disease.

Yes, getting severe COVID-19 -and possibly dying- was rare, but it was definitely happening and that of course what everyone understands. And yes, many people hardly have any symptoms when they get COVID-19, and that’s what everyone hopes will be their outcome if they contract COVID-19. But I was seeing mostly the third group of COVID-19 patients whose illnesses were the ones that really instilled fear in me. These were healthy people who contracted COVID-19, and then had unusual symptoms. I saw a young person who just finished their 14 day quarantine for COVID-19 and now was having a heart attack. Then there was the young person who had just been diagnosed with COVID-19 and now was having a stroke. There was my friend, an athletic 50 year old, who continues to this day to have exercise tolerance since his COVID-19 diagnosis 6 months ago. Personally I was seeing about 8-10 COVID-19 patients a shift, interspersed with the garden variety ER patient. And day after day, seeing this volume of formerly healthy patients now dealing with significant enough illness to come to the ER was reason enough to get myself vaccinated. Yes, the odds are very low that I would be hospitalized or die if I got COVID-19; but the odds are much higher that I will have to miss work, have medical bills, and have chronic problems such as clotting or long term shortness of breath. This is what sets COVID-19 apart from the flu. The flu is quite predictable - three to 5 days of fever and myalgias then improvement; no clotting, no strokes, no long term shortness of breath. But with COVID-19 it is all unknown and unpredictable.

People were SICK and they were requiring admission for extensive hospital stays because COVID-19 related infections aren’t easily treated in a few days. Knowing that hospitalized patients wouldn’t be allowed visitors during their prolonged hospitalized was another stressor we dealt with as caregivers. Patients understand they can’t have visitors, but they don’t understand that if they deteriorate, they might die… alone. We understood that because we saw it happen. If you are the unlucky doctor who has to intubate (put the breathing tube in) a COVID-19 patient, you might be the last person they ever speak to, the last person whose eyes they look into. That was a difficult and tragic realization for the physicians who were intubating COVID-19 patients as well as for the staff who cared for the patients in the hospital.

The ER wait times were getting longer and the waiting room was packed day after day. There weren’t enough staff - nurses, techs, lab technicians, radiology technicians, etc - to get things accomplished and this created extreme situations. This time the fear was not as much fear for our own lives but fear for others. We were protected but they are very sick. Confusion and frustration combined with physical and mental fatigue exacerbated the stress that I was experiencing. When will this end? We don’t have enough rooms for all these patients. Wait, there are no more non-invasive breathing (high flow) machines for my cardiac patient? Oh no! A few days later we were announcing that we were practicing Crisis Standards of Care, essentially meaning that patients may not get the care they would if the resources were available. That was a horrifying moment to not only realize that after more than 15 months on the frontlines, your ability to care for patients properly wasn’t getting easier but was getting harder. I saw more and more exhaustion set in in the staff around me. Compassion fatigue is a real thing for real reasons. As doctors we are here to help others, and specifically as emergency medicine physicians we are here to help others when their bodies are trying to die. Watching someone die in front of you, someone who you thought you could have somehow saved, is a depressing, lonely feeling, one that lasts longer than I care to admit.

6. ENDEMIC

We’re not off this mountain yet, but at least we’re on the other side of this peak. As the virus mutates, there will be more variants. I heard there’s a pill that can cure COVID-19. Wow! Wouldn’t that be nice? I hope it’s true, I hope it works, and I really hope people will want to take it. Despite the extreme mental, and emotional and sometimes physical exhaustion that I experienced during this pandemic I do still have hope for a tomorrow where we won’t live in fear of COVID-19, where we can work in the ER without double masking for 10 solid hours, and where people see eye to eye more often than they don’t.

WHEN WE WERE HEROES

-

Juan the HUC

-

Dr. Jaime Butler

-

Brian Security

-

Nancy RN

-

Steve Potter

-

Dr. Cliff Ellingson

-

Banu RN

-

Natalie

-

COVID Self Portrait #2

-

Dr. Anne Zink

-

Rachel RN

-

Dr. Gina Wilson-Ramirez

-

We've Got This

PREPARING FOR A PANDEMIC

-

Night Delivery

-

Old N-95

-

Bull with a COVID N-95 Mask

-

Bull with Green Covid Mask

-

Re Used N-95

-

Paper Bag System

-

Kirkland Brand Toilet Paper

-

Drive Thru Test Center

-

Lake Otis Pharmacy and the Drive Thru Test Center

PPE PROBLEMS

-

IT'S RIPPING OUT MY EARRING

-

IT'S RIPPING OFF MY EAR

-

I CAN'T HEAR YOU

-

WHERE'S THE COFFEE?

-

MASK-NE

-

IT'S RIPPING THE SKIN OFF MY FACE

-

Fogged Up

A VACCINE IS COMING

-

CopacaSami

-

Tabletop Joy

-

Happiness

-

Overflowing

-

Vaccine Exuberance

THE BATTLE RAGES ON

-

Emergency Use Authorization

-

Dr. Victor Zalenko

-

Compassion Fatigue

-

Intubation

-

Crisis Standards of Care

ENDEMIC

-

Hope